In this edition of Insights with Ian, we dive into one of aquaculture’s most misunderstood topics: genetics.

From pedigree-based section to genomic innovations, Ian explains how these strategies are shaping the next generation of fish farming and why understanding them is critical for staying competitive.

Selection vs. Modification? The Future of Genetics

This post deals with the complex and often-confusing fields of conventional and unconventional breeding, both of which rely heavily on biotechnology. A diversity of conventional breeding techniques are used to produce stock for finfish aquaculture. Simply selecting the “best” individuals for breeding based on growth, shape or colour may initially produce spectacular trait improvements but will not work over the long-term. This is because initial gains are unsustainable and may reverse after a few generations due to the accumulation of inbreeding (mating between closely related individuals). The missing ingredient is genetics.

So, what is genetic selection?

There are several types of genetic selection including mass selection, family or pedigree-based selection, genomic selection, and marker assisted selection. For sustainable breeding, the founding population (genetic nucleus) should have enough unrelated individuals so that inbreeding can be managed over the long-term and with sufficient genetic variation to allow meaningful genetic gain in commercially important traits. Conventional genetic selection can be viewed as a managed version of natural processes.

Pedigree-based selection is very effective and widely used. For highly heritable traits, such body size at harvest age, compounded gains of 8-15% per generation can be achieved resulting in shorter production cycles or larger fish for sale. The genetic nucleus therefore becomes increasingly valuable with each generation. High levels of biosecurity are therefore required to safeguard past investment in genetic improvement. Broodstock hatcheries are usually found in remote places far away from production facilities (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 New Zealand King Salmon broodstock hatchery at Tākaka, South Island is in a beautiful but isolated location.

For species such as salmonids, carps and many others, gametes are isolated from mature fish and fertilised in vitro to produce individual targeted crosses. In other species, including breams and snappers, social interactions are required for maturation and so spawning occurs naturally in groups. In this case, the nucleus is split between breeding tanks containing combinations of individuals chosen to keep inbreeding to acceptable limits whilst still achieving high rates genetic gain.

To drive genetic gain, the next generation of parents are chosen from a representative sample of offspring reared under production conditions (the evaluation group). Fish are genotyped and phenotyped at harvest to allow pedigree construction and the genetic merit of individuals to be assessed in terms of an Estimated Breeding Value (EBV): the expected performance of its offspring. Multiple traits are combined in a Selection Index, a single score combining the EBVs for each trait, weighted according to the EBV accuracy and economic importance of each trait. The more traits that are included, the lower the gain in each individual trait.

Traits which are hard to change with genetic selection are not worth including in the Index. EBVs become more accurate as the pedigree becomes more extensive. The rate of genetic gain per generation also increases with the accuracy and range of phenotypic values, the heritability of the trait, prediction accuracy, selection intensity, and a reduction in generation interval. Inbreeding acts as a drag on genetic progress. Digitalisation and direct data entry, which eliminate transcription errors, and efficient mating plan software also contribute to the amount of genetic gain that can be achieved.

The optimal mating plan is one that maximises EBVs whilst maintaining inbreeding and co-ancestry at safe levels. It is apparent from this brief description that conventional selection gives breeding programme managers many different options to accelerate genetic progress.

Genomic Selection (GS) differs from purely pedigree-based selection in that it uses many thousands of genetic markers to more accurately estimate the relationships between animals. GS is particularly suitable for complex traits controlled by many small-effect genes, such as disease resistance and growth. High-density SNP arrays or Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) enable the genotyping of tens of thousands of markers distributed across the genome. The high-density, 50-70K SNP chips typically used are very expensive to develop unless bought in high volumes, which has restricted their use to large companies. For small producers, cost-effective GS alternatives have been developed which involve genotyping the more numerous offspring with relatively cheap lower density panels (3-5K SNPs) and the parents at high-density. The missing genotypes in the offspring are then imputed from the parents with accuracies of >95%. Multispecies genotyping arrays are another strategy used by genetic service providers to reduce costs for their customers by combining sample volumes across multiple species as well as breeding programmes.

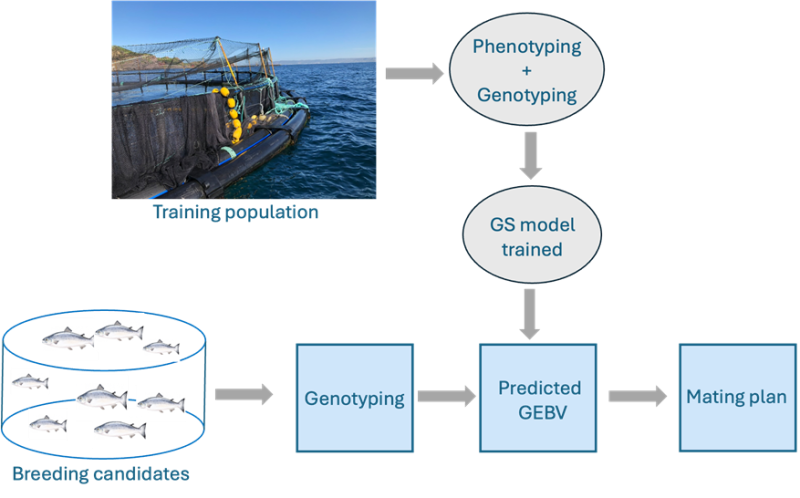

With GS a training population is phenotyped (measured for target traits) and genotyped (Fig. 2). The data is used to create a prediction equation using statistical models to estimate the effects of genetic markers on traits. Prediction accuracy is limited by the complexity of genetic architectures and environmental interactions and is often somewhat higher than for purely pedigree-based methods. Most (BLUP)-based Models assume equal SNP effects and include the widely used G-BLUP. Modified weighted models can also take into account QTLs (Quantitative Trait Loci). Single-step genomic BLUP (ssGBLUP) is a popular method for calculating estimated breeding values in livestock using genotyped and non-genotyped animals by combining both pedigree and genomic relationships. It is of particular interest in the age of phenomics where massive amounts of phenotype data are available e.g. from video recordings. Bayesian Models tend to have higher accuracy for traits with major QTLs but are computationally intensive. Machine Learning Models are flexible, use large datasets and are good at capturing complex relationships but require careful optimization. Academics are also exploring the integration of multi-omics data and structural variations (e.g., CNVs) into current models with variable results.

Fig. 2 The different steps involved in genomic selection in fish breeding

The next step is to genotype breeding candidates at high density and calculate Genomic Estimated Breeding Values (GEBVs) from the prediction equation (Fig. 2). It is important to stress that whilst genomic predictions may be highly accurate, their advantage can only be exploited with a sufficiently large pool of breeding candidates to allow high selection intensity. Finally, GEBVs, co-ancestry and inbreeding values are used to construct the mating plan in the same way as for purely pedigree-based methods.

Genomic selection in its current form is not about finding or knowing the genes responsible for a particular trait. Marker Assisted Selection (MAS) is used to make breeding decisions under some circumstances. With the reduction of DNA sequencing costs Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS) have become commonplace. Most traits of interest have a complex architecture and genetic variation across several chromosomes is needed to explain the observed phenotypic variation. Individual genetic loci in this case only contribute a small a percentage of phenotypic variation and are unsuitable for MAS even if they have statistically significant effects. Furthermore, associations discovered in one population may not be present in another population due to genetic differentiation between isolated populations. There are however some notable exceptions including Cardiac Myopathy Syndrome, Pancreatic Disease and Infectious Pancreatic Necrosis (IPN) resistance in Atlantic salmon. For example, an elegant series of experiments has established the causal SNPs responsible for IPN resistance. MAS for IPN resistance in commercial breeding programmes has seen a dramatic decrease in economic losses in freshwater. MAS may not be a forever solution because of the evolutionary arms race between host and pathogen. This arms race is stacked in favour of the bacterial or viral pathogen which benefit from shorter generation times and larger population sizes. Already there are reports of viral strains that appear to have escaped the original resistance mechanism to IPN.

How does Genetic Modification differ from Genetic Selection?

Livestock selection has been going on for thousands of years since our ancestors first settled and began farming. With traditional or conventional selection, the genome is gradually altered through the choice of breeding candidates over many generations. In contrast, there are two quiet distinct non-conventional methods of animal improvement namely transgenesis (GMOs) and genetic engineering (GE) which seek to modify the genome in a single or few generations. This may sound attractive but comes with many challenges.

Transgenesis refers to the use of genetic engineering methods to insert genes from one organism into another with the aim of altering function. Genetic engineering methods are widely used in research and have been critical for advancing fundamental knowledge of molecular process. The use of transgenesis to produce Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) in agriculture though has proved highly controversial and a matter for intense public debate. In the United States GMO’s are regulated under the Coordinated Framework for Regulation of Biotechnology by the USDA, FDA, and EPA to ensure that any transgenic organism brought to market is safe to eat and poses no threat to the environment including wildlife. In the case of animals, welfare standards are also an important consideration. Even more restrictive regulations are in place in the European Union such that no species of GMO animal has ever been granted a license. GMO salmon have been licensed and approved for sale in the USA and Canada but proved a salutary lesson for investors.

The AquaAdvantage Salmon Story

AquaAdvantage was an Atlantic salmon developed by AquaBounty Technologies in 1989 which were genetically engineered to have faster year-round growth than normal salmon. The growth hormone regulated gene in Atlantic salmon was replaced by the equivalent gene from a Chinook salmon and a promoter sequence from ocean pout. Backcrossing produced a stable GE salmon line which could be triplodised to become sterile. It took until 2015 and millions of dollars to gain regulatory approval from the FDA. Rearing of GMOs had to be carried out in a physically contained freshwater containment facility. A test facility was constructed in Indiana in 2018 and AquaBounty became a public company in 2019. In January 2022, the company announced plans to build a commercial facility in Ohio and the share price reached a high of U$23 dollars.

However, by the end of the year the shares dropped to 65 cents and to avoid delisting from the NASDAQ there was a 20 shares into one share consolidation. Primarily due to lack of consumer demand for GMO salmon the Ohio plant was never built, and the company went into liquidation in 2024. The last of their facilities on Prince Edward Island, Canada were sold to Cooke Aquaculture in 2025.

Gene editing is the other non-conventional method used in breeding involving the targeted modification of specific DNA bases. Since this does not involve introducing genes from another species it quite different from the AquaAdvantage salmon. Uses of the technology range from replacing a single deleterious SNP with a normal one, to precise deletions or insertions in the DNA sequence. The most widely used technology is CRISPR/CAS 9 often called “genetic scissors”, a discovery which in 2020 earned the Nobel Prize for Chemistry for Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna. CRISPR/Cas9 uses a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) to identify specific DNA sequences creating a double-stranded break at the target site. The break can be repaired by non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) leading to gene knockout or Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) involving using a repair template to introduce precise changes to the sequence. Multiple genes can be edited simultaneously potentially enabling the genetic improvement of complex traits.

Genetically engineered seeds for plant crops such as cotton, soybean, and corn were approved in the United States by the USDA as early as 1996, resulting in herbicide-tolerant and insect-resistant varieties. Dozens of other GE field crops are widely grown in the United States and countries such as Brazil and Japan. In stark contrast, the European Union decided to ban the field trials needed for commercialisation of GE. Although the Commission voted to relax its rules in 2024 these changes have yet to be ratified by member states.

There has been extensive research on gene editing in animals, but few practical applications or examples of commercialisation to date. Human medicine is leading the way by developing genetic engineering solutions for uncurable or difficult to treat diseases, helping to increase public acceptance of the technology. For example, gene editing has resulted in a cure for sickle cell disease and the treatment of rare inherited genetic diseases in newborn babies. The slow application of GE in farm animals in the United States is in part related to the very thorough and onerous regulatory approval process operated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to ensure safety. There is a rigorous regime of testing to ensure that edits are completely specific and have no impacts on animal health, environment, food safety or quality.

Only in 2025 did the FDA approved the first major licensing of a gene edited farm animal, paving the way for its commercialisation over the next few years. This significant breakthrough was made by PIC, a Genus company, and involved the development a pig which is resistant to the devastating Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS) virus for which there was no known cure or effective vaccine. The PRRS virus causes breathing difficulties, fever, inability to eat, stillborn piglets and can result in death and costs the global hog industry more than U$1billion/year. PRRS resistant pigs are identical to non-gene edited pigs in all other respects whilst offering advantages in terms of improved welfare, reduced use of the antibiotics used to treat secondary infections, and more sustainable farming practices. The Governments of Argentina, Brazil, Columbia and the Dominican Republic have joined the FDA in approving the gene edit for PRRS resistant pigs and regulatory approval is currently being sought in other countries including Canada, China, Japan and Mexico.

In aquaculture, CRISPR-edited tiger puffer and red sea bream with enhanced growth were approved for sale in the Japanese market in 2021. Disruption of the appetite controlling leptin receptor in tiger puffer fish led to increased feeding and resulted. In 1.9 times faster growth rate than non-GE fish. Growth enhancement in red sea bream was achieved by the knockout of the myostatin gene – a member of the large Transforming Growth Factor gene family and a negative regulator of muscle growth. The Centre for Aquaculture Technologies and Brazilian Fish have also produced a gene edited Nile tilapia with a disrupted myostatin gene. GE individuals show up to 40% faster growth than non-GE fish. Published pictures of myostatin knockouts show an unattractive bloated appearance compared to normal fish. GE projects focused on growth are some years from commercialisation and the public appetite for such products remains to be tested.

The escape of fish from net pens following storm damage is a significant environmental issue. Regulatory conditions for the approval of GE fish will almost certainly require sterility to prevent interbreeding of escapees with wild populations. Sterility can be achieved using triploids or by disrupting genes required for germ cell specification and migration such as Dead end. This can be achieved by GE or through gene silencing technology involving the batch incubation of eggs with antisense morpholinos.

Perspective and Final Thoughts

Most traits can be improved effectively using the well proven classical genetic selection methods. GE projects do have a place in aquaculture breeding but are very high risk for investors given the considerable amounts of time and money required to reach commercialisation and the uncertain returns.

In my opinion, the GE projects most likely to succeed commercially are those focused on traits which cannot easily be improved by genetic selection or other means including, vaccines, medicines, feeding regimes, diets, husbandry and harvesting practices. GE projects which lead to improved animal welfare, environmental benefits and/or more sustainable farming are likely to be favoured by regulators and the public. Some authors classify mass selection, family selection, genomic selection and non-traditional methods such as genetic engineering in terms of a numbered developmental series which implies increasing merit. However, from a commercial perspective only the return on investment (ROI) matters.

In my view, the optimal genetic improvement strategy is the one that produces the greatest ROI, and this will not always be the newest or most complex and expensive solution.